Using ImageMagick to generate anti-aliased bitmap fonts for a microcontroller's LCD display

In an earlier article I explained how to

use the FreeType library to display nicely-rendered, anti-aliased text

on the framebuffer of an embedded Linux system. Linux systems usually

have enough RAM to do the font rendering, and some kind of storage

device to hold the font data.

In an earlier article I explained how to

use the FreeType library to display nicely-rendered, anti-aliased text

on the framebuffer of an embedded Linux system. Linux systems usually

have enough RAM to do the font rendering, and some kind of storage

device to hold the font data.

But what about microcontroller applications, which might have only one thousandth the RAM and storage of a typical single-board Linux unit? At one time the question of display quality would not arise, because these devices displayed on a monochrome dot matrix device, or even a seven-segment LED display. These days, however, manufacturers are making high-resolution, full-colour displays for microcontrollers like the Arduino and Raspberry Pi Pico. I have written elsewhere about using a 320x480 LCD with the Pico.

Note:

The method I'm describing in this article works for microcontroller applications written in C/C++. It could probably be adapted for other programming languages but, to be honest, I think it would be awkward.

With a display like this, better display quality can be achieved than simply dumping a set of monochrome bitmap glyphs onto the display device. In particular, we can use anti-aliasing to smooth the edge of the glyphs. Anti-aliasing works by writing intermediate brightness values at selected points on the outline of the character, so give the impression that there are more display pixels than there really are. It's a widely-used technique, and one that rendering libraries like FreeType handle automatically.

Monochrome bitmap fonts circulate widely on the Internet. Anti-aliased bitmap fonts less so. What's required is a way to generate the relevant font data, and a way to include it in the microcontroller application, probably along with the application binary. Some microcontroller applications will uses an external storage device (SD card, for example) but ideally we need a system that will work without one.

Assuming that we want to handle (at least) the ASCII character set, we need an approach that is fully automated -- we don't want to be manually cutting-and-pasting character glyphs from one software tool to another.

In this article I describe the general approach I use to embedding anti-aliased fonts in a microcontroller application. I won't be showing any source code; as ever, there is a full sample application in my GitHub repository.

Note:

The sample applicaion displays text on a Linux framebuffer, so it can be seen working on a regular desktop Linux system. That isn't the intended application of this article -- there are far nicer ways to render text on Linux.

The general approach

My general approach uses bitmapped fonts stored in JPEG format in the binary of the microcontroller application. To get the data into the binary, I write it as a (computer generated) C source file, and compile it into the code.

Why JPEG? JPEG compression gives about an 80% storage reduction for greyscale font glyphs, with little perceptible loss of quality. Decompressors for JPEG are widely available, some that will work in the highly resource-constrained environment of a microcontroller. In the example program that accompanies this article I use a public-domain JPEG decompressor library that requires only about 256 bytes of RAM.

The example program uses a 54x94-pixel Courier font. Uncompressed, each glyph would require about 5 kB of storage, so the complete set of ASCII printable characters would require about half a megabyte. Some microcontrollers don't even have this much non-volatile storage. The Pi Pico has 2Mb of flash ROM, so it could accommodate a couple of uncompressed fonts, so long as the application itself does not need much.

With JPEG compression, this same font uses about 100kB of storage, which is a more manageable value.

Of course, the compromise here is with speed. Every character that is displayed must be uncompressed first. Speed could perhaps be improved by caching some number of uncompressed glyphs in RAM. The problem, of course, is that microcontrollers typically have little RAM. I'll discuss this issue more later.

I've found in practice that the overhead of JPEG decompression is manageable on a Pi Pico, provided the application isn't writing pages and pages of text. At any rate, it's worth it for the much-reduced storage.

The ImageMagick convert utility will generate JPEG images

(and most other kinds of image) from user-specific text strings.

Why generate the fonts as C source code? GCC provides a way to embed binary data directly into an executable, which is certainly quicker than compiling an enormous C source file full of font data. The program with embedding the binary data directly is that it's not a technique that works very well for many small files. You'd still have to write code that selected the correct block of data to match a particular character, and the compiler doesn't organize the data in a way that makes this easy. The GCC binary embedding method works well for including a small number of large (perhaps even huge) files, but it isn't ideal for this application.

By generating C source files, we can also include in the generated

files all the data structures

needed for the application to be able to locate each glyph's

data and meta-data. Of course, to use an approach like this, we

need a tool to turn binary data into compilable C code.

xsd -i is such a utility.

Note:

In this article I'm mostly describing the use of fixed-pitch fonts, just because they are easy to handle. The method could be extended to support variable-pitch fonts by storing an indicator of width along with each font glyph. However, I won't be describing how to do that here.

Using ImageMagick

This command will generate a JPEG file containing a single, anti-aliased character -- an X in this case.

convert -background black -fill white -colorspace Gray -font courier-bold \ -pointsize 72 label:X X.jpg

-colorspace Gray causes the utility to output a greyscale

JPEG file, rather than colour. In practice, because of the way JEPG works,

we don't save a huge amount of storage this way -- about 20% -- but there's

no need to store colour information in a font -- the application can always

colour the text programmatically if it needs to.

Note that it's not easy (at least, not to me) to work out the relationship

between the -pointsize argument and the pixel size of the

resulting image. I've found that some trial-and-error is required here.

On my system, a 72-point Courier Bold character is about 94x54 pixels

in size.

A complication that I did not expect is that ImageMagick does not generate images of the same width even with fixed-pitch fonts. I do not know if there is a way to make it do so -- after all, 'fixed' should mean exactly that. The differences are small, but can't be ignored -- when decompressing the fonts we need to ensure that we have reserved enough memory to decompress into. For simplicity, my sample program just works out the largest character in the set of characters generated, and stores that size so it can be used at runtime.

I use a Perl script to do all the font generation (makefont.pl

in the example program). It's a bit fiddly because many of the characters

that we want to generate have a specific meaning to a Perl program:

care has to be taken with characters like " and /.

Still, these are matters of Perl programming, not font handling,

so I won't go into them further (see the source code for more details).

Using xsd

The command

xsd -i x.jpg

outputs a C array definition containing all the data in x.jpg,

like this:

unsigned char x_jpg[] = {

0xff, 0xd8, 0xff, 0xe0, 0x00, 0x10, 0x4a, 0x46, 0x49, 0x46, 0x00, 0x01,...

unsigned int x_jpg_len = 1343;

Each character's array array will contain 700-1500 bytes so, if we append the data for every character into a single C source file, that file will be very large. Still, modern C compilers don't seem to have any problem dealing with very large source files, and I prefer this approach over trying to compile and link nearly a hundred separate files.

The xsd utility also outputs a length for the array it

generates. The makefont.pl utility generates arrays

that contain pointers to each character's own array and size,

so the application program can readily find the data for a specific character,

and how long the compressed data is.

Decompression at runtime

So the above is, in outline, what needs to be done to generate the JPEG font definitions in C. Of course, there are many fine details that I haven't gone into, but the source code demonstrates these.

The main runtime problem faced by the sample application is that of decompressing the JEPG data. We also have the problems of finding the data for a specific glyph in memory, and also of transferring the uncompressed data to the display device. The first problem is illustrated better in the source code than I could describe it in text. The problem of outputting to a display depends entirely on the display device in use. I can't really say more about that, because of the huge range of display devices on the market.

To decompress the glyph data we need a JPEG decompressor. The

libjpeg library is ubiquitous, but I haven't had any success with

it on a microcontroller -- it simply uses too much RAM. However, there

are other libraries, some of which are specifically designed for resource-constrained system. In the sample program I use PicoJPEG by

Rich Geldreic and Chris Phoenix. This decompressor uses only a few hundred

bytes of RAM, regardless of the image size. PicoJPEG is much less versatile

than libjpeg, but that's irrelevant here, since we have the

luxury of being able to generate

the JPEG files in a format it can handle. Another nice feature of

PicoJPEG is that it externalizes the process of reading the compressed

data -- it doesn't assume that it will be stored in a file. The concept

of 'file' may be meaningless in a microcontroller, and it's not relevant

in this application at all, when all the font data will be in ROM.

A choice needs to be made between decompressing the font glyphs directly onto the display device, or decompressing to memory first. The first approach has the benefit of using no additional memory; on some systems that will be crucial. However, it does mean that we have to update the display on a pixel-by-pixel basis. Most microcontroller displays use SPI or I2C interfaces that are comparatively slow to transmit data. Updating such a display pixel-by-pixel will incur significant overheads. These displays are much faster to update in blocks but, of course, there needs to be enough RAM to store a block. The sample program allocates enough RAM to store one complete glyph, and decompresses to that.

There's a subtle complication related to anti-aliasing that needs to be

considered here, when deciding how to update the display. Bear in

mind that the makefont utility generates white text on

black background. It isn't difficult to change the text or background

colours to suit a different display background. However, if you're

writing text over an existing background image, you'll have

to consider how you will merge the font data with the existing

background. It's tempting to simply ignore the 'black' pixels in the

font data, and leave the corresponding pixels in the display with their

existing colours -- but this looks terrible.

Another issue to consider is the caching of decompressed glyphs. Obviously, it will be faster if we don't have to decompress JPEG for each character written to the display. If the controller has some RAM free, it could maintain a cache of decompressed glyphs. However, deciding which characters to cache could itself take a certain amount of computation; it isn't clear to me, given the meagre RAM available to most microcontrollers, that there's much benefit in caching.

There isn't space to going into all these issues of display rendering here -- I only mention them because they will need to be taken into account in a real application.

How it looks

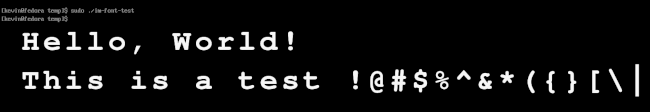

The following screenshot shows the output of the sample application, rendering to a Linux framebuffer.

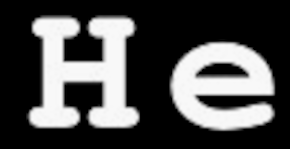

Here is the first couple of characters, zoomed four times, so that the effective of anti-aliasing can be more easily be seen.

On a desktop Linux system the display is generated so quickly as to be effectively instantaneous. On a Pi Pico we see the text being drawn, but it's still broadly acceptable, at least for displays that are not updated very frequently.

Closing remarks

Showing anti-aliased text on a microcontroller's display is a challenge, and a relatively new one: it's only recently that that suitably capable display devices have been available at low cost. The method I describe in this article is far from elegant, but it seems to work. It could easily be expanded to handle character sets other than ASCII although, of course, the larger the character set, the greater the storage requirements.

Have you posted something in response to this page?

Feel free to send a webmention

to notify me, giving the URL of the blog or page that refers to

this one.