They don’t make ’em like that any more: Borland Turbo Pascal 7

Borland’s Turbo Pascal was one of the most successful programming tools of all time. It introduced development techniques, such as integrated source-level debugging, that we take for granted today; but which were radical at the time.

TP 7, also known as Turbo Pascal for Windows 1.5, was the pinnacle of the Turbo Pascal line, and its end. The name ‘Turbo’ was associated with what were regarded as hobbyist products – ‘Borland Pascal’ was a different, much more expensive, product. But Turbo Pascal was enough for some quite substantial applications, and was very affordable. It was also ‘book licensed’, which I think was a new thing in the software industry. You could buy one copy of TP, and any number of people could use it – but only one at a time. Even when it was distributed on floppy disks, there was no copy protection. (Turbo) Pascal eventually gave way to Delphi which, despite its technical merits, never had the same impact.

I used TP 7 to write medical imaging software back in the 90s, to run under Windows 3.1 – which was a great operating system in its day. Like previous releases, Windows 3.1 was still, essentially, an extension to MSDOS, but with clever tricks to allow it to multitask (after a fashion) and address more memory. It had a simple, consistent user interface model – both for the user and the programmer. It had, at that time, none of the wasteful and irritating anti-features that have come to make modern Windows so depressing to use. So Windows 3.1 was a platform we all wanted our applications to support – not that there were many alternatives at that time.

Like many other programmers, I learned the Pascal programming language specifically to use TP 7 – I was essentially a C programmer in those days, but programming for Windows in C was a horrible job. Frankly, it’s scarcely better today. It was, and is, necessary to combine a whole stack of command-line tools that take incomprehensible text files as input. TP 7 automated and concealed all that nastiness.

It wasn’t just the tools that were a problem: the user interface model was, essentially, object-oriented; but C did not make it easy to program in an object-oriented way. TP 5 had introduced basic object-oriented concepts to the Pascal language, and these were were to prove essential. The Windows-specific features were provided by something called Object Windows Library: a relatively thick, object-oriented wrapper around the basic Windows C API. My recollection is that Borland introduced an object-oriented programming library for Microsoft Windows before Microsoft did – and Borland’s was better.

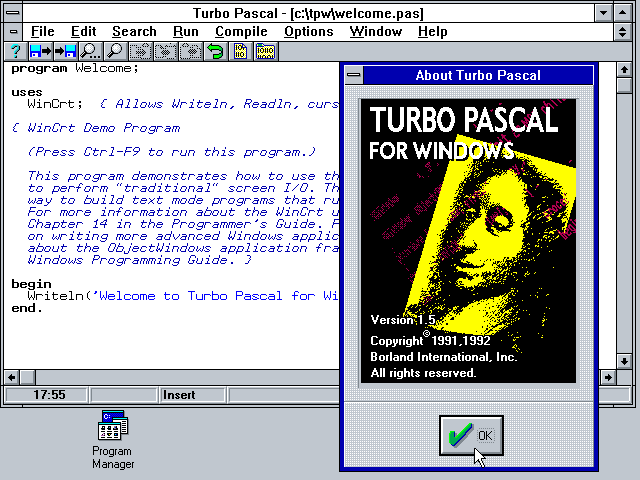

OWL made it easy to create nice-looking user interfaces, with a bit of eye candy. The familiar ‘green tick button’ was an OWL enhancement, which graced so many Windows applications that it eventually became an irritating cliche.

All, in all, It was much easier to program for Windows using Turbo Pascal 7 than with anything else. Not only did it provide a programming model that matched the way the Windows user interface worked, the application itself had a Windows graphical interface – many Windows programming tools at that time actually ran under MSDOS, and were entirely text-based. TP 7 also had fully-graphical tools for designing the user interface elements, like menus and icons. Laying out a menu using a definition file with an obscure format, using Windows Notepad, was never an agreeable experience. Microsoft did produce graphical tools for this kind of operation, but Turbo Pascal combined them into a seamless IDE. All I had to do to build and run my programs was to hit the F7 key. I could even set breakpoints for the debugger, just by clicking a line of code. As I said, common enough today, but revolutionary for early Windows programming.

But what really made TP 7 special was its CP/M heritage. Turbo Pascal came to Windows by way of CP/M and MSDOS, which meant it had a compiler core that was designed to run with tight memory and a comparatively slow CPU. In the days when most compilers had to write a stack of intermediate files on disk, TP just constructed everything in memory. It did this using highly-optimized code, written in assembly language, by very skilled people. It doesn’t matter much today if your compiler spits out a heap of temporary files, because disk storage is fast and cheap. But in the days of the floppy disk, you had to minimize disk access. Unfortunately, you also had to minimize memory use, because there wasn’t much of that, either. Programming for CP/M took real skill and dedication.

So when TP came to Windows machines, with their 16-bit CPUs and megabytes of RAM, it was like an early Christmas for developers. A compiler designed to be adequate with 32kB of RAM and a single floppy drive will positively fly when given megabytes and a hard disk.

All this meant that TP 7 was a joy to use. It was like a modern IDE, but without any of the bloat. Developers who would never have tackled Windows programming with Microsoft tools were able to move from MSDOS to Windows without too much difficulty – even if they first had to learn Pascal, as I did. The compiled code was pretty speedy but, if it wasn’t brisk enough, you could write assembly language directly in the Pascal source files.

I don’t think it’s too much of an exaggeration to claim that Turbo Pascal contributed to the widespread uptake, and eventual domination, of Microsoft Windows on desktop PCs. If there had been a ‘Turbo Pascal for Linux’ in the early 90s, then we might all be running Linux on our desktops today.

So what happened to Turbo Pascal? Three things, at least, contributed to its eventual downfall.

First, there was increasing competition from the C programming language. Borland did produce a Turbo C, and later a Turbo C++, but they weren’t as influential as Pascal. It’s easy to forget that PCs weren’t the first general-purpose computing devices. Most scientific and educational establishments, and many businesses, used graphical workstations and a central minicomputer. C was already well-established in these environments before desktop computers started to become prominent. And before that we had mainframes and terminals – but that was a different world, where Fortran and COBOL ruled.

Most ‘serious’ PC applications were written in assembly language in the early days, as they had been for CP/M – the low resources almost necessitated this. Minicomputers were not so limited, so compilers were more practicable, even in the 1980s. So when compilers started to become of interest to microcomputer developers, there was almost no reason to favour one programming language over another. Pascal could have become the standard programming language for the PC. That it did not, I think, reflects the fact that many software companies that had been active in industrial and scientific computing saw an opportunity in PCs, and tried to move into that market. These companies already had substantial experience with C, and they brought their preferences with them. So while I was happy to learn a new programming language to develop for Windows, a software business with a thousand staff might not have wanted to take that step.

The second factor, I think, was the increasing palatability of Microsoft’s C tools. Microsoft did eventually produce an IDE of its own and, of course, Microsoft controlled the Windows platform. I don’t think Microsoft’s C IDEs ever became as easy to use as Borland’s, but they probably didn’t have to, given Microsoft’s position.

Third, Microsoft’s Visual BASIC started to attact small-scale and bespoke developers. BASIC was already a staple of the microcomputing world, because it was easy to learn, and did not require a separate compilation step. Attaching bits of BASIC code to Windows user interface elements was an efficient way to produce relatively simple, small-volume applications.

I loathed Visual BASIC in the 90s, and I loathed it until the day VB6 drew its last laboured, wheezing breath in 2005. Still, I can’t deny its popularity, and I’m sure that many of the same people who were drawn to Turbo Pascal were later drawn to Visual BASIC, for much the same reasons. VB lowered the barriers to entry into Windows programming in the same way that TP had previously done. Arguably it lowered them too much, but let’s not go there today.

Early versions of Turbo Pascal are now freely, and legally, available. Retrocomputing enthusiasts with an interest in early PCs and MSDOS are well catered for. So far as I know, however, TP 7 remains somebody’s intellectual property, although it isn’t entirely clear whose. It probably comes into the category of ‘abandonware’ but, to be frank, it’s not all that important: it can’t produce code that runs on modern Windows systems, and few people have much interest in early Windows – it’s just not retro enough.

So that’s Turbo Pascal: a colossus of the microcomputing world, which faded and died largely unlamented. It always was a creature of its time – it prospered for the brief period when microcomputers were limited enough to reward skilled development, but widespread enough to create a substantial market for programmers. By the time it started to become difficult to find enough highly-skilled programmers to satisfy the market needs, it didn’t matter: computers were getting powerful enough to make good our limitations as programmers. That almost nobody has the skills these days to implement something like TP is something we could eventually come to regret – or, rather, our grandchildren could. Software development is becoming a semi-skilled industry, and I doubt that the rise of AI will entirely compensate for this.

But who needs a Turbo Pascal, when you have 128Gb of RAM attached to an 5GHz CPU, for a hastily-written, bloated Java program to burn?

Have you posted something in response to this page?

Feel free to send a webmention

to notify me, giving the URL of the blog or page that refers to

this one.