They don’t make them like that any more: the Yamaha DX7 keyboard

The sound of the Yamaha DX7 synthesizer defined 1980s popular music. While the DX7 could, in principle, produce a limitless range of sound textures, few musicians used more than the 32 built-in present sounds. As a result, the sound of the DX7 is immediately recognizable. For me, the theme from the TV show Twin Peaks typifies the DX7 sound but, frankly, you’ll be hard-pressed to find a successful album from the mid-80s where you don’t hear it. It would be pointless to list the bands and artists that used the DX7 – it would be easier to make a list of the ones that didn’t. I’m told that the ‘Electric Piano 1’ preset alone appeared in over 60% of album releases of 1986.

The original, Mark I DX7 was a huge, uncompromising lump of ironwork, made to be thrown in the back of a van. Its membrane keypad controls were horrible to use, but were good at resisting beer spills. When you turned up for practice with a DX7, everybody knew you meant business.

What made the DX7 special was its novel approach to sound generation. Although electronic keyboards were not new when the DX7 was released in 1983, they nearly all used an analog method of sound production. Typically an electronic oscillator would generate a tone whose pitch was set by the key pressed, and then a variety of filters and amplitude modifiers would work on the sound to change its properties.

This is a completely logical way to approach simulating real musical instruments electronically. Real instruments have something that generates a tone – reed, string, whatever – and something that modifies the characteristics of the tone – pipe, soundbox, and so on. Each instrument has a characteristic amplitude envelope. For example, a note on a piano has an initial louder, percussive peak in volume, followed by a gradual decay. Analog synthesizers tried to simulate these acoustic properties using electronics.

Most analog synthesizers of the 70s and early 80s were monophonic, that is, they could only play one note at a time. Hitting a new key while the sound of the first was playing would simply cut off the original tone. You couldn’t play chords on an analog synthesizer, which made it a ‘lead’ instrument in popular music – something that carried a distinct tune rather than providing an accompaniment.

Synthesizer designers capitalized on this role, by providing their instruments with expression wheels, which the musician would operate with the left hand, while playing the melody with the right. These wheels could vary the pitch of the note, like ‘bending’ the string on a guitar, or alter the characteristic of a filter. A good-quality analog synthesizer like the infamous Minimoog was as expressive as a guitar or a violin and, frankly, easier to become proficient with. The Minimoog was the signature sound of 1970 ‘prog’ rock. The DX7 continued the tradition of expression wheels, as other instruments did, and some still do.

Building an analog synthesizer that was polyphonic – where many keys could be played at the same time – was stupendously expensive. The same electronic circuitry had to be duplicated many times, sometimes for each key. These instruments were mostly of academic interest in the 70s – I can’t think of many bands that were routinely using one on stage before the 80s.

The DX7 worked in a completely different way from the analog synthesizers of the 70s. First, it was all-digital. But it didn’t try to simulate digitally the tone generation methods of existing analog synthesizers. Conceptually, the basis of its sound generation was frequency modulation. That is, one sinewave tone generator modified the pitch of another, which perhaps modified the pitch of another. If this kind of modulation is at a low frequency, the result is a rather conventional vibrato effect. In the DX7, though, the tones that modulated one another were all in the audible range, producing an effect that was not at all conventional.

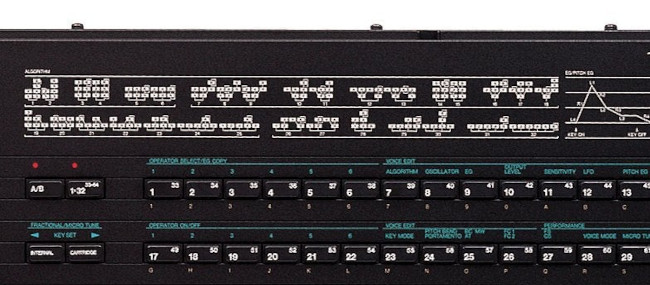

The frequency modulator components in the DX7 were called operators. For each of the sixteen notes that the instrument could play polyphonically, there were six of these operators, making 96 in all. The DX7 could combine the operators in many different ways, with the output of one feeding the inputs of others. These arrangements of operators were known as ‘algorithms’. The standard algorithms were shown on the top of the DX7’s cabinet, as you can see in the photo below.

Algorithms 31 and 32 have all the operators contributing directly to the output. Setting the pitches of the six operators to different multiples of the basic note pitch produced the kinds of sound that could be produced by a draw-bar organ, but with somewhat more flexibility, as each operator could be programmed with a different amplitude envelope.

The more novel sounds, however, came from algorithms in which the operators all modified one another. Algorithms 16-18 all take their final output from a single operator, whose pitch gets modified by the other five operators, all interacting with one another.

As a result, the DX7 could produce everything from smooth, organ-like sounds, to abrasive, ringing electronic sounds that we had never heard before.

I said that the DX7 used frequency modulation ‘conceptually’. The reality was that the tone generation was completely mathematical. Custom-made micro-controllers did the math digitally, and fed the result to a digital-to-analog converter. The sampling rate of the instrument as a whole was about 60kHz, allowing for frequencies beyond the limit of human hearing. It was this prevalence of high-frequency components, I guess, that gave the DX7 it’s signature ‘brilliant’ sound.

Yamaha’s ‘operator’ technology eventually spread outside the DX7, particularly to PC sound cards. An interesting development was the discovery that, if the operators started with square, rather than sine, waveforms, it didn’t take as many operators to create interesting sounds. Yamaha went on to market two-operator and four-operator sound chips – the OPL2 and OPL3 respectively; the latter was part of the hugely popular SoundBlaster 16 sound card.

In 1984 Yamaha released the CX5M – a complete music composition workstation that included an operator synthesis module. The CX5M was a remarkable piece of equipment in its own right. I owned one myself in the late 80s and, while I’d like to write an article about it for this series, I was stoned out of my tree for the whole time I had it, and don’t remember much about it.

Yamaha went on to sell 150,000 of the original DX7s – a staggering number for a keyboard instrument: ten times as many as the Minimoog, which was itself considered popular. The DX7 was was not cheap – in the UK it sold for £1300 in 1983 (equivalent to about £5000 in 2024) – but it was still a whole lot cheaper than a polyphonic analog synthesizer.

The DX7, for all its success, had some oddities.

The instrument was praised for it’s ‘brilliant’ sound but, weirdly, that brilliance diminished for notes at the right-hand end of the keyboard – the highest octave could sound somewhat dull. Possibly this was the result of careless design of the digital-to-analog converter (DAC) but, given the care that Yamaha took with the rest of the design, I suspect the DAC had to be tuned this way to overcome limitations elsewhere in the processing chain.

For example, the DX7 only had a 12-bit DAC. It would definitely have made the math easier and faster, if the designers had anticipated that it only had to produce a result to 12-bit precision. 16-bit DACs were available in 1983, because this is the format used by audio CDs. So I guess the limitation was in the internal computation, not the choice of DAC itself. But I don’t know for sure.

The real problem with the DX7, though, was programming it – which is why almost nobody did. Partly the limitation was the user interface, which had only a two-line display, and all the push-buttons had at least four functions. But mostly it was almost impossible to work out how to configure the operators to get a particular sound. The tiniest change in the settings could have a radical effect on the output. Analog synthesizers were never particular good at generating the sounds of real instruments, but at least we could predict what the effect of tweaking a control would be. With the DX7 it was a lottery.

What most people did – certainly what I did – was to fiddle with the settings more-or-less at random, and then store any configuration that sounded good. You could give the sound configuration a name, which would have been handy, if anybody had the patience to enter a name using the horrible membrane keypad. You could save your sound configurations to a memory cartridge, which meant that you could use somebody else’s DX7 – perhaps one in a recording studio – with your own settings. I certainly remember trading DX7 cartridges with other keyboard players, back in the day.

Yamaha did produce further models in the DX7 line-up. The Mark IID was notable for having a split keyboard, so you could assign different sounds to different parts of the keyboard. It also used a 16-bit DAC. Whether the internal math used a higher precision, or Yamaha just realized they’d used an inferior DAC in earlier models, I don’t know. A potential advantage of the later models was that they had real mechanical controls, not the nasty membrane keypad of the Mark I. Whether they were as beer-resistant, I don’t know. There was even a model with a floppy disk drive.

Sadly, none of these later models enjoyed even close to the success of the Mark I, and the decline of the range was almost as rapid as its rise had been. I bought my Mark I DX7 second-hand in 1990 for a few hundred quid. I was still playing it in bands until the mid-90s, by which time it was already a historical curiosity.

What killed the DX7, and other instruments like it, was the falling cost of microprocessors and memory. Yamaha’s FM synthesis was arcane, but it was comparatively easy to implement with the digital technology of the early 80s. Given how successful analog synthesizers like the Minimoog had been, it’s interesting to speculate why instrument designers like Yamaha didn’t try to model analog sound generation digitally. This would have been much more comprehensible to musicians than FM synthesis. The answer, I think, is that technology was not ready for that in the early 80s.

When technology did reach that point, it had become possible to do sound synthesis using sampling techniques. The use of mathematics to produce sounds resembling real instruments quickly became obsolete once we could just go out and sample the real thing. Sampling is a boring, brute-force approach to sound synthesis, but it’s a relatively straightforward one, now we have the computing power and memory.

And once we have sampling technology, there’s little point using computational techniques to make the once-novel sounds of earlier synthesizers: we can just sample the instruments themselves.

There remains a niche interest in generating instrumental sounds using mathematical modelling, but almost all digital music production these days is based on sampling. My Kawai stage piano has about forty different instrumental sounds, all produced from samples of real instruments. Apart from the string sounds: I believe it creates those by tormenting cats on Xanax.

With hindsight, the DX7 and its ilk look like a weird diversion in the path of musical progress. Operator synthesis makes no logical sense. It became popular because we had the capability to do digital sound generation, but lacked the technology to do it in a comprehensible, systematic way. So the DX7 enjoyed huge popularity for a few years, before fading into obscurity.

If you want the sound of a DX7 from your modern keyboard on stage, it’s easier to sample a real one, than to do the math that the DX7 did. For studio work, you can get software DX7 emulators for popular audio workstations. This allows us to create all-new DX7-style sounds, which is something we can’t do using sample.

Oddly, though, anything produced by operator synthesis sounds like Brian Eno.

Have you posted something in response to this page?

Feel free to send a webmention

to notify me, giving the URL of the blog or page that refers to

this one.