How Microsoft Windows killed the palmtop computer

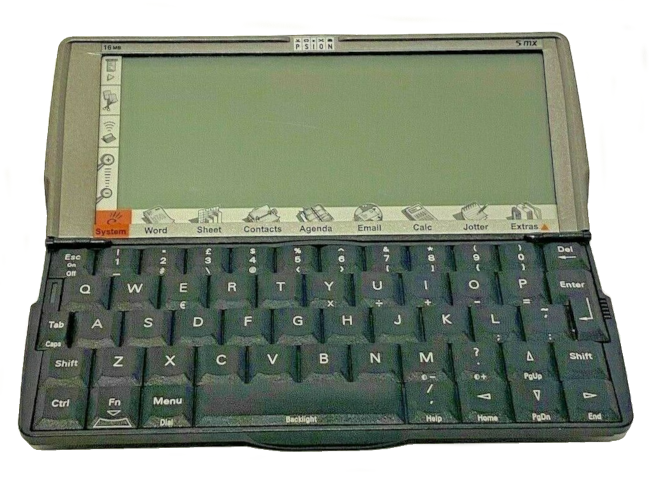

I've been wondering lately why palmtop computers like the Psion 5, which were technologically perfect, had such a short production life. It's not just the Psion 5 -- a number of products in the same technological space achieved a high degree of perfection but, not only did the individual products fade away, the entire palmtop industry did. Why?

If I was not the first Psion 5 MX owner in the UK, I'm sure I was one of the first. I recall riding my motorcycle sixty-odd miles around the M25 in a blizzard of horizontal rain to buy it. This was in the summer of 1999. I'd heard a rumour that a shipment from Psion had arrived, containing just one MX unit, to a lock-up in Woking. To raise the rather considerable sum of money to buy it, I'd recently sold my Psion 3 -- at my own wedding, no less.

It was a shady business transaction -- I had to keep out of view of my wife, as she had just become, as she stood sipping champagne with the normal people. That I had been carrying a palmtop computer whilst taking my wedding vows really says all you need to know about me.

What is it about this little gadget, that would make a reasonably well-balanced person go to such lengths to obtain one?

When I referred to the "perfection" of this device a while ago, that wasn't just flowery language. What made the Psion 5 so special was that every part of it had been designed from scratch, to suit a very specific purpose. It had a "real" keyboard, that completely filled the bottom half of the case -- not the horrible "chiclet" keyboard that plagued most portable devices, and still does. You could actually type documents on it -- not in a cramped, finger-busting way, but with real touch-typing.

Every piece of software in the Psion 5 was written from scratch, including the operating system. This was EPOC32, which eventually became Symbian. I don't think I ever wrote software for EPOC, although I certainly did for Symbian. It was never an agreeable experience, but no worse than programming for Android -- a task that has absolutely nothing to recommend it.

All the built-in applications in the Psion 5 were also perfect. They had been written to be a precise match for the keyboard and screen, and everything just worked. Although the screen was tiny, by modern standards, everything was sized properly on the display, and all the most frequently-used functions were accessible using a single key-press.

Best of all, with care I could get a month of modest usage from a single pair of AA batteries -- say, one hour a day. This concern for energy-efficiency is something we seem completely to have abandoned. The tragedy of this neglect is not lost on me, as I sit in front of a fan in the middle of the hottest temperatures every recorded in the UK. That we -- billions of us -- are willing to turn our planet into a steaming, scorching wasteland just so we never miss a tweet is something our distant descendants will look back on with bewilderment.

If we have any.

The Psion 5 had a serial RS232 for connecting to a modem or printer, and a compact flash (CF) slot for storage expansion. The CF slot was, and remains, the best way to exchange data between the Psion 5 and a desktop computer. There was a Windows application called "PsiWin" that was supposed to synchronize with desktop applications. This worked when it felt like it, and it felt like it only occasionally. It doesn't work with modern Windows releases, anyway.

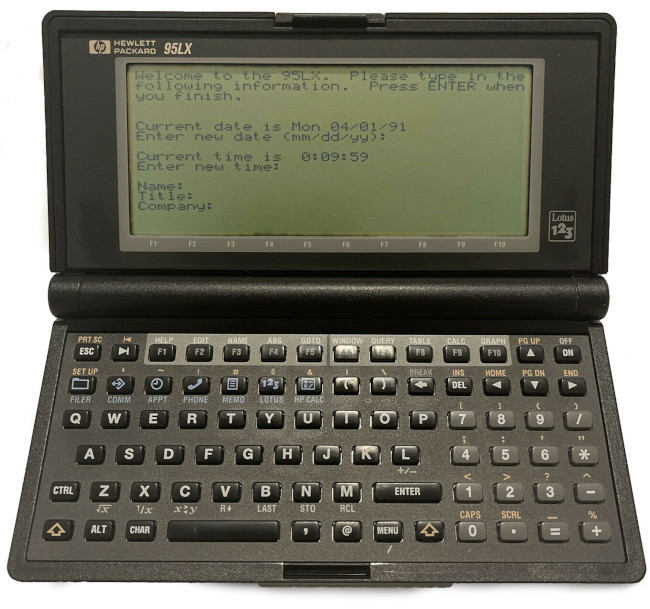

Of course, the Psion range was not the first, or last, palmtop computer. At about the same time that the Psion 3 was released, HP released the 95LX. Unlike the Psion, the 95LX ran MS-DOS. It certainly ran Lotus 1-2-3 very effectively -- it was essentially designed to do just that. Although, in principle, the use of MS-DOS provided access to a much greater range of applications than Psion's proprietary plaform, the reality was rather different. In practice, even early MS-DOS software tended to exceed the capabilities of the HP palmtop, particularly its low-resolution screen. Nevertheless, the 95LX offered a month's use on a single pair of AA batteries, and ran the software written specifically for it very effectively.

There were also commendable efforts from the likes of Sharp and Atari -- the Atari Portfolio was probably the first recognizable palmtop computer, released in 1989.

We didn't know it at the time but, by 1999, the Psion 5X was the pinnacle of palmtop computing. It wasn't the last palmtop computer, but it was the last perfect palmtop. HP continued to produce palmtops of increasing sophistication; the last mainstream model was the Journada 720 in 2002. Psion did produce a Psion 7, but it was a notebook computer, rather than a palmtop. As such, it was in direct competition with full-sized laptops, which offered faster CPUs and more storage. The Psion 7 was not a success, in the UK at least.

So what happened to palmtops? Why did they decline so rapidly?

One of the main culprits -- indirectly -- was Microsoft Windows. By 1999 Windows was already established as the dominant desktop operating system in much of the world -- Windows 95 for home users, and Windows 3.5 for business. It's certainly understandable that manufacturers of portable computers would want to provide compatibility with Windows.

Unfortunately, Windows was far too resource-intensive for the portable computers of the 90s. Windows CE, which was supposed to solve these problems, was never very satisfactory. While HP did produce palmtops that ran Windows CE, they never had the popularity that the earlier MS-DOS devices enjoyed.

Psion's decline can also be attributed, again indirectly, to Windows. Psion devices never ran Windows but, by 1999, Windows was attracting nearly all the developers of consumer software in the world. Psion's proprietary platform was not appealing to developers outside the Company, because far more sales were to be made in the Windows marketplace.

Windows never had much of a presence in pocket computing, despite Microsoft's effort to break into that market. In 1999, if you wanted to run Windows on a small computer, you needed a laptop. At this time, laptops were just becoming practicable -- a decent laptop was reasonably affordable, and just about portable. It turned out that people were willing to find the money, and develop the shoulder muscles, just to run Windows. And that was the end of the palmtop. Pocket computing did not fade away -- it became dominated, as it still is, by the hugely unsatisfactory smartphone.

Of course, there's a reason why palmtops were so popular: in the few years of their heyday they worked really well. There's something to be said for being able to carry a real computer, with a real keyboard, in your pocket. So, for enthusiasts at least, it's good that Linux is available. Unlike Windows, Linux offers the prospect of a reasonable desktop operating system that can run, in principle, on the limited hardware of an ultra-portable device. Android, for all its faults, has proven that.

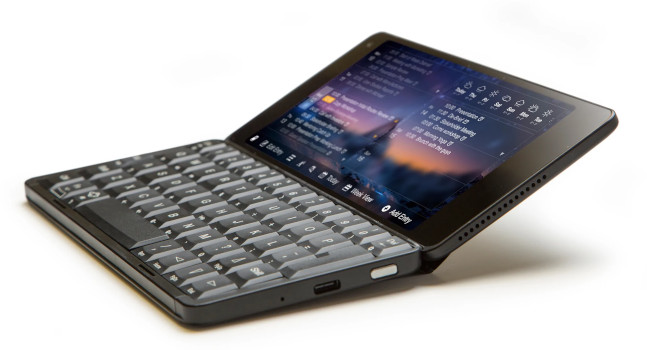

Consequently, we are seeing the first rumblings of a resurgence in the palmtop computer market. Most of these new devices, like the FxTec Pro1 are little more than smartphones with hardware keyboards -- and rather meagre keyboards at that. However, the spiritual successor of the Psion 5 might be the Planet Gemini. If this device looks like a Psion 5 with a colour display, that's no coincidence -- some of the original Psion designers are involved in the development of the new device.

The Gemini is -- for better or worse -- primarily designed to run Android. However, it seems to be possible to install a real Linux distribution instead. How effective it will be at running mainstream desktop Linux applications like LibreOffice, Gimp, and VLC remains unclear at present.

Sadly, none of the modern palmtop offerings will run for a month on a pair of AA batteries. So much for the worse for the planet.

Have you posted something in response to this page?

Feel free to send a webmention

to notify me, giving the URL of the blog or page that refers to

this one.