Predicting eclipses with clockwork

In my retrocomputing articles I normally look at computing and electronics between 1970 and about 2000. In this article, just for a change, I’ll be looking back about 2300 years, to a mechanical computer – the Antikythera Mechanism.

The story of the discovery of this device in a shipwreck by pearl divers is well-known, and I won’t go into it here.

Over the last hundred years or so we’ve achieved what we believe is a reasonable understanding of how this device worked and, to a lesser extent, how it was used. This is a remarkable feat in itself, considering that the surviving mechanical parts are gummed together by two millennia of seabed accretions.

I’m a little sceptical of the claim that the Antikythera Mechanism was used for navigation. Although it’s clearly a computing device, my feeling is that was more likely used on the desktop, like an orrery – a mechanical model of the motions of the moon and planets. The makers of the Mechanism probably had an Earth-centered view of the Solar System, which makes computing the movements of the planets even more difficult than it is with our modern understanding. The gearing that was used to model the apparent motion of the planets – if we have understood it correctly – is truly remarkable.

In this article, however, I will tackle something a little simpler: using a clockwork device to predict eclipses of the Sun and Moon. It’s almost certain that the Mechanism was used this way – the clue is the gear wheel with 223 teeth that can be seen in the photo above. I’ll explain why this number is significant later. It turns out that modelling eclipses without celestial mechanics is not conceptually all that difficult – provided we have acute observational skill and extraordinary patience over decades.

How we get eclipses

Let’s start by looking at how we get eclipses in the first place.

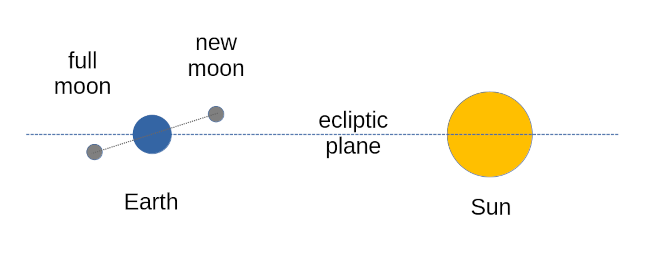

To get a solar eclipse of any kind, the Sun, Moon, and Earth must be approximately in a line, with the Moon between the Sun and the Earth (see diagram below). To get a lunar eclipse, the Earth must be between the Sun and the Moon. The time when the Moon lies between the Sun and the Earth we call ‘new moon’. At this time, the Moon is not generally visible from the Earth, because there’s nothing to illuminate the face that we can normally see. At new moon, we’ll only see the moon at all when it happens to be causing an eclipse.

If a solar eclipse can only happen at new moon, then a lunar eclipse can only happen at full moon. So, very often, we’ll see a solar eclipse at the new moon following a lunar eclipse. I’ll explain why this is important later.

The time between consecutive new moons is called the synodic month, and it’s about 29.5 Earth days in duration.

The Earth and all the other planets of our solar system orbit the Sun in what is very close to a plane. That is, we could put them all on a (very large) flat surface. We call this plane the ecliptic. If the Moon also orbited the Earth in this plane, then we’d see an eclipse every synodic month – a solar eclipse at new moon and a lunar eclipse at full moon. But that isn’t the case – the orbit of the Moon around the Earth is inclined at about 5 degrees to the ecliptic. So, while it has to be new moon to see a solar eclipse, we won’t see one every new moon. In nearly all cases, the Moon will be too far from the ecliptic for its shadow to fall on the Earth. The drawing below shows this situation, where the tilt of the Moon’s orbit at a particular time makes it unlikely that there will be any eclipse, even at new moon or full moon.

The points at which the orbit of the Moon crosses the ecliptic are called its orbital nodes. There are two – a rising node, and a falling node. The time bateween nodes is called the draconic month, and it’s about 27.2 Earth days. That the draconic and synodic months are nearly the same is, presumably, just a coincidence.

Note

In case you were wondering, draconic is indeed related to ‘dragon’. In mythology, a lunar eclipse was envisaged as a dragon ‘eating’ the Moon.

So to see some kind of eclipse, at least the following conditions must apply:

It must be new moon (for a solar eclipse) or full moon (for a lunar eclipse).

The Moon must lie close to one of its nodes; that is, it must lie close to the ecliptic plane. It doesn’t have to be stop-on; how far from the ecliptic the Moon can be, and still cast a visible shadow on the Earth, depends on a number of other factors.

One of those other factors is how far from the Earth the Moon is, at the time under consideration. For a solar eclipse, the further away the Moon is from the Earth, the larger the shadow it will cast, and the more extensive the area from which the eclipse can be seen. The Moon’s orbit around the Earth is elliptical; the closest point is called perigee, the furthest apogee. The time between successive apogees is called the anomalistic month, and is about 27.6 Earth days. It’s very similar to the draconian month of 27.2 days. Again, this is probably just a coincidence.

So, for the purposes of eclipse prediction, there are three different kinds of month that we must consider:

| Month name | Description | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Synodic month | Time between consecutive new moons | 29.53 Earth days |

| Draconic month | Time between Moon’s consecutive crossing of its rising node | 27.21 Earth days |

| Anomalistic month | Time between consecutive perigees | 27.55 Earth days |

Basic eclipse prediction

If I see a solar eclipse of some sort today, at my location, then my next strong chance of seeing an eclipse is in six synodic months’ time. In that time the moon will have completed approximately six draconic months, and be close to the ecliptic plain again (it’s actually about 6.4 draconic months, because the draconic month is a little shorter than the synodic). You might think that the best chance to see an eclipse would be a whole number of draconic months since the last eclipse, because the moon’s orbit will be crossing the ecliptic again, and in line with the Earth and the Sun. But, no – we only see solar eclipses at all on or near new moon, and lunar eclipses at full moon. Remember that the Moon must not only be near the ecliptic, but it must be in line with the Earth and the Sun as well.

But six synodic months later is not the only time we might see an eclipse.

Suppose that, during the today’s eclipse, the Moon was just below the ecliptic. At the next new moon, it will be just above the ecliptic. That is, it might still be at a point where it could cast a shadow on the Earth, and cause an eclipse somewhere. But two synodic months later, the Moon will definitely be too far out of line.

Similarly, if six months from now the Moon was just able to produce an eclipse, being just at the limit of its position with respect to the ecliptic, then conceivably there might be an eclipse a (synodic) month earlier – five synodic months from today.

It turns out that, in practice, if there’s an eclipse today, the next eclipse – if there is one – will probably be six synodic months away. Less likely, but still worth considering, are intervals of five and six synodic months.

So, essentially, mechanical eclipse prediction comes down to timing synodic months – the phases of the Moon.

There’s a lot of probabilistic qualifications in the preceding discussion: what if we want to be sure when the next eclipse will be? Is that even possible?

The saros cycle

The best prediction of an eclipse so far seems to be ‘six synodic months from the last one’. Maybe. Can we do better? In modern times we certainly can, because we have accurate mathematical models of our solar system. But how would the ancients have done it?

The key is to find how many synodic months have to pass before a whole number – or close to whole number – of draconic months have passed. At this point we will again be at new moon, with the moon at or close to the ecliptic.

As a bonus, it would help if the Earth-Moon distance were the same at this point in time as it was at the initial point, because that factor dictates the size of the shadow cast on the Earth or the Moon.

The synodic, draconic, and anomalistic months are not multiples of

one another and, because they are so similar in duration, it will take a

long time (perhaps forever) before the Earth, Moon, and Sun are in the

exact same alignment again. If we look for an alignment where a

whole number of synodic, draconic, and anomalistic months all occur

within a 24-hour period, it turns out that 223 synodic months, which

is

6585.32 days, is almost exactly the same as 242 draconic months –

6585.36 days, and 239 anomalistic months – 6585.54 days. It’s not a

perfect alignment, but we have to wait a long time to find a better one.

If we want the alignment to be within a period of a couple of hours,

we’ll have to wait 3263 synodic months, which is about 263 years.

Note

I don’t know if there’s a way to calculate these time periods analytically. I wrote a program to do it.

Note

It’s worth bearing in mind that looking for closer alignments is probably unprofitable – the figures for the lengths of the various lunar months are averages, not exact. There’s probably no way to perform a more exact calculation.

The period of 223 synodic months is called a saros. Although this term is derived from ancient sources, it turns out that its use in the context of eclipse prediction only dates back to 1686. It was used this way by Edmond Halley (of comet fame), but whether the ancients used it in the same way is contested. That the ancients could predict eclipses is not contested – just the terminology.

It turns out that, if there’s an eclipse today, we can be reasonably certain that there will be an eclipse with similar characteristics (same duration, same area of coverage) in 223 synodic months. Unfortunately, 223 synodic months is not a whole number of Earth days. It’s about 18 years, but it’s eight hours away from the nearest whole number of days. What that means is that, although the Moon will case the same kind of shadow on the Earth (for a solar eclipse), different parts of the Earth will be affected.

If we’re using as our initial, reference eclipse an event where the coverage area on the Earth was large (so the Moon was at its furthest from the Earth) then it’s plausible that a particular location will see both eclipses – today’s, and the one eighteen years later. After all, a total solar eclipse with the Sun at apogee can darken a whole continent. But, as an ancient astronomer, I’d do better to look at lunar eclipses. I will already have noticed that a solar eclipse that I do see was preceded by a lunar eclipse in the same synodic month; it would seem reasonable to conclude that most or all lunar eclipses are followed by a solar eclipse somewhere on Earth. And it turns out that lunar eclipses are much easier to see from Earth than are solar eclipses – and not just because different regions of the Earth are in shadow. It’s actually very difficult to see a modest partial eclipse of the sun, because it’s not safe to look directly at it. But there are no such problems with the Moon.

So it turns out that the saros interval of about 18 years gives us a really good way to predict eclipses. But we already know that there are far more eclipses than that. If there’s an eclipse today, there’s possibly going to be one in six synodic months’ time – that’s less than half a year, and a lot shorter than 18 years.

But here’s the crucial point: the saros cycle is quite repetitive. If I see an eclipse today, and another a synodic month later, I can be almost certain that I will see an eclipse a saros period later, and one synodic month after that. Moreover, the type of eclipse will be similar. So if I can collect 18 years’-worth of eclipse data, I have everything I need to predict eclipses with reasonable accuracy for hundreds of years to come.

The importance of observation on repetitive phenomena

We know that the ancient Greeks, and before them the Chaldeans, could predict eclipses. We also know that they didn’t have modern computers. What they did have was an understanding that natural phenomena repeated, and a lot of patience. They almost certainly came upon the saros cycle by making astronomical observations for many decades, or even centuries. Our ancient forebears were as interested in the skies as we are – perhaps even more. After all, the positions of the Sun and Moon had a direct impact on agriculture, weather, and tides.

How do we do all this with clockwork?

Most likely none of us has seen a mechanical timepiece with an ‘eclipse’ dial. What we do sometimes still see, and is instructive to consider, is a ‘moon phase’ dial on a mechanical clock or watch. If we can display moon phases, a suitable reduction gearing will be able to drive a pointer with a saros cycle. So the problem is not different in kind, only in engineering complexity.

The slowest-moving gear in a conventional watch is the hour gear, which usually makes a full rotation every twelve hours. So to display the moon phase we need a gear that rotates 29.53 times, for every two rotations of the hour gear. Or, alternatively, 59.06 times for each rotation of the hour gear.

If we accept a small amount of inaccuracy, we can round this to 59 revolutions of the hour gear for one revolution of the moon phase gear. Implementing a gear ratio of 59:1 is easy enough if you have a way to make a ‘finger’ gear – essentially a gear with only one tooth. The complete gear mechanism is a one-tooth finger gear meshing with a gear with 59 teeth. This is, in fact, the way that modern mechanical watches display moon phase.

This gearing will be accurate to about one part in a thousand. So the

moon phase display would slip about one day every 2.7 years. A

mechanical moon phase display would have to be wrong by at least a day

or so, to be completely useless. So this clock would track moon phase

reasonably accurately for

2-3 years, before the moon dial needed to be reset.

Could we get better precision with a mechanical gearbox? Certainly: we can get a gear ratio of 59.04 using three coupled gear ratios: 20:72, into 16:41, into 10:64. The more exact ratio 59.06, but I couldn’t come up with a way to implement that, using a modest number of gears with modest tooth counts. Still, my three-step gearing would be accurate to three parts in ten thousand, so should handle moon phases tolerably well for twenty years or so. We could achieve better accuracy, if needed, using more gears.

To implement a complete saros cycle display requires, in simplistic terms, dividing down the moon phase gear by 223:1 (because there are 223 synodic months in the complete cycle) or, perhaps, dividing down the day gear by 6585.32.

It seems, however, that this isn’t the way the original Antikythera Mechanism worked. Although it probably did have a display of Moon phase, it appears that it was derived, not by a simple down-gearing of the number of days, but by a subtraction process based on the draconic month and the apparent motion of the Sun around the Earth. After all, it is this combination of the Earth-Sun and Earth-Moon motions that makes the synodic and draconic months.

Whether this method of calculation is more accurate, or just more expedient, I don’t know (but probably somebody does).

Closing remarks

The complexity of the Antikythera Mechanism, and the single-mindedness that its builders must have needed to collect the astronomical data to implement it, has lead some people to propose that it was built by visitors from space. Or, alternatively, that it’s a modern fake, like the rash of crystal skulls that appeared in the 1960.

For sure, there’s nothing really like the AM – nothing we have so far discovered from that time period, anyway. But there are scattered ancient writings that allude to complex machinery, and there’s no doubt that astronomy was an obsessive interest for many ancient cultures – just look at the astronomical alignments embodied in Stonehenge.

The reason I don’t feel the same sense of awe and wonder when I look back on, for example, the Z80 microprocessor is that I lived through most of the technological developments that produced it. Yes, I’m old enough to remember when integrated circuits were rejected by many engineers as the Devil’s work.

When our entire civilization has been submerged by the rising waters of the melting ice caps, will our distant descendants find a ZX81 while diving for pearls? And, if they do, will they respect and admire our ingenuity, or claim that such a thing must have been gifted to us by aliens?

I wonder.

Have you posted something in response to this page?

Feel free to send a webmention

to notify me, giving the URL of the blog or page that refers to

this one.