They don’t make them like that any more: Denshi block electronics kits

I’ve been fascinated by electronics for as long as I can remember – my interest certainly started before my parents would have trusted me with a soldering iron or more than three volts. For a child to have such an interest wasn’t that unusual back in the 70s: there wasn’t the same barrage of passive entertainment available to children in those pre-internet days. Without something to occupy our minds, my infant friends and I would have been playing war games in the drainage culverts, and risking drowning.

So, instead, from about the age of three I was trying to connect bulbs and batteries with wires, just to see what would happen. Eventually I moved on to transistors and resistors, but not integrated circuits – not in those days.

For more sophisticated electronics experimentation of this kind, the usual platform was a ‘spring clip’ electronics kit, of the kind sold by Radio Shack (Tandy, in the UK) under the ‘Science Fair’ brand.

In these kits the electronic components were fastened rigidly to a baseboard, with their terminal brought out to spring clips. To carry out experiments, we used lengths of wire to join the spring clips, following detailed instructions. Each connection followed a route of a different length, so the kits included pre-trimmed wires in various lengths. In practice, the trimmed ends would eventually fail, and the wires would have to be re-trimmed, creating an opportunity to slice off piece of a finger. I have to confess that I’ve done the same thing more than once in my adult life as well, when I’ve too impatient to fetch the proper wire-stripping tool.

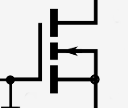

The problem with these kits – well, where do I start? Educationally the main problem was that the thing you assembled bore no visual relationship to the electronic circuit as it was drawn. If anybody had drawn the circuit as it got constructed, it would have been incomprehensible, like a diagram of a bird’s nest. Because the relationship between function and structure was unclear, assembling the circuit was an exercise in painstaking instruction-following – “connect terminal 42 to terminal 6…” – rather than comprehension of the theory. Troubleshooting was, as you might imagine, a nightmare.

Still, these Science Fair kits did allow for some interesting constructions: AM radios, amplifiers, telegraphy devices, light-sensitive alarms, and so on. As the only moving parts were the wires, the kit would last forever, so long as you could trim new wires when the old ones broke. The springs themselves did eventually get sloppy, but you could generally find a place to put a wire that still had a bit of tension.

To be fair to Radio Shack, their instructions were clear, written by a native English speaker, and they explained the design principles in detail. But, as you could assemble a circuit without understanding it – in fact, the construction method more-or-less necessitated this approach – the kit was only educational if you took the trouble to read all the documentation. I did, as an aspiring geek, but I doubt I understood much at ten years of age. The worst drawback, though, was that assembling circuits with spring clips and flying wires was tedious and error-prone.

So my mind was blown when I first came across a Gakken ‘denshi block’ kit, although I wasn’t to know that’s what it was for many years. A sketchy-looking chap was selling these from a barrow in a village market, squeezed between other disreputable fellows selling imitation leather jackets and meat products that had started to smell. The kit wasn’t expensive, even by pocket-money standards, although I can’t remember how much I paid for it in 1976. £2, perhaps.

I didn’t know at the time that the kit I had purchased was the bottom-of-the-range model, nor that it was already discontinued by the manufacturer – but subsequent events made that likely, as I’ll explain.

The kit consisted of a plastic base-plate into which were cut slots in a rectangular grid. Into this base you could slot the ‘denshi’ blocks themselves. Each block was a clear plastic box about 1cm square and about 2cm tall, containing a single component – transistor, resistor, capacitor, etc. Later kits would have blocks containing only wires, but mine had the wires as separate metal clips that plugged into the base.

‘Denshi’ is a Japanese word that translates loosely as ‘electronic’. I didn’t realize at the time that these kits were made in Japan, although it was clear that the instructions hadn’t been written by anybody who had English as a first language. I learned later that they were produced by the Gakken company, and they were a genuine innovation.

The denshi system radically reduced the tedium, and increased the success rate, of assembling circuits. Not only was physical process of assembly quicker and less error-prone, what you assembled actually looked like the electronic circuit as conventionally diagrammed.

Although it isn’t clear in the photo, the electrical connections on the denshi blocks emerge from the bottom of each block. Electrical contact is made when two connectors are forced against one another in the slot in the baseboard. It wasn’t a reliable means of connection over the long term and, eventually, the contacts had to be bent slightly outwards to restore connectivity. This clearly carried the risk of snapping the contact off the block completely but, somehow, I managed to avoid this.

Gakken’s later ‘EX’ range of kits used a different means of connection, which can be seen in the photo below. For reasons I’ve never understood, the new plastic was tinted, making the internal component less visible. Perhaps the blocks were cheaper to manufacture in this colour?

These blocks were not held onto the baseboard by their contacts, as had been the case in the SR kits. Instead they had corner cut-outs that engaged with pegs, as can be seen in the photo below. The electrical connectors were sprung, so the combination of the connectors and the pegs made a solid assembly.

Another difference between the EX kits and the earlier SR series was that the new kits had a kind of console that contained more sophisticated (and not user-modifiable) components. In particular, the tuned circuit for radio designs wasn’t a plug-in block in the EX kits, but was built into the console, which also contained an amplifier and a voltmeter, along with the battery. The SR kits had these either as blocks, or just as external parts that had to be wired to the baseboard using cables.

I had two favourite circuits for my SR-2A kit. The first was a simple microphone amplifier. I could hide the loudspeaker in a sibling’s bedroom, and project my voice into the room from a distance, causing intense irritation.

My other favourite circuit was an FM transmitter – probably illegal. It had enough range that I could over-ride BBC radio broadcasts in the house, replacing them either with my own jabbering, or the output of a my cassette player.

Eventually, while assembling one of the radio circuits, I connected one of the transistor blocks the wrong way around, and burned it out. I was upset about this but, when I returned to the market and found the seller nowhere in evidence, I was distraught. My parents suggested I write to the manufacturer, and see if they could supply a replacement. It turned out that Gakken was based in Japan, but they had a UK distributor. I can’t remember the name of this company, but they earned my life-long affection. I was hoping at best to get a replacement transistor but, in fact, within a week they sent me, free of charge, a huge bag of denshi blocks and baseboards. With hindsight, I suspect it was the rest of their UK stock – the SR range had already been discontinued by this time.

With these extra parts, and the assistance of better-informed relatives, I was able to construct things far beyond the original scope of the kit, and elevate my ability to irritate my family to a whole new level.

The Gakken kits eventually became more sophisticated, including logic gates and, eventually, a microcontroller. I never had one of these kits, though. Not only would it have been far beyond my purchasing power in the 70s, by the time integrated circuits had become widely available I had graduated to soldering circuits on strip-board. The first time I had to solder up a 14-pin DIP IC, I cooked about a dozen of them before I learned how to do it, or that there was such a thing as an IC socket. Sadly, I’m even worse at this job fifty years later because, well, because I’m fifty years older.

Denshi blocks, along with my youth and good eyesight, are a fading memory. By about 1980, kids had found more interesting ways to spend their time: home computers for the geeky ones, and video games for the rest. When I was a teenager, I was interested in making electronic stuff because, apart from it being an interesting pass-time, building it was cheaper than buying it. I could make a perfectly serviceable stereo amplifier for about a tenth the price of the slinky, brushed-aluminium article in the hi-fi shop. Now, of course, that’s not true: improvements in mass production have made it cheaper to buy finished goods than components for anything that has a mass market. So it’s not just denshi blocks that have faded away, but electronics kits of any kind.

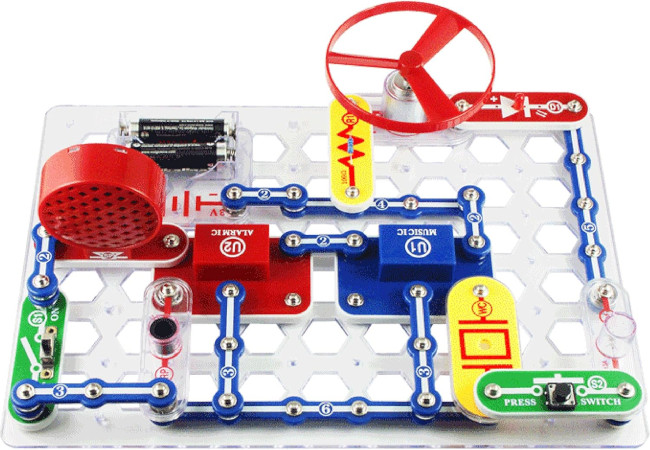

The best we have these days are the dumbed-down, garish toy-like products such as the “Snap Circuits” offering shown below. Superficially these resemble denshi blocks, in that they have moveable components with push-together contacts. Like the Science Fair and denshi kits they have switches, motors, and batteries. What they don’t seem to have is any connection to electronic theory – I’m sure they’re educational to some extent, but I doubt you’d learn how a reflex radio circuit works.

Geeky kids these days aren’t interested in transistors, and why should they be, when you can pack a million of them into a microcontroller chip? Contemporary geeks – and not just young ones – are drawn to the Raspberry Pi, Arduino, or micro:bit ecosystems. Arguably, learning about these things is more productive in the modern world than understanding the behaviour of a tuned circuit; it’s also more likely to broaden your employment opportunities.

The denshi block is a part of my childhood, as was the Raleigh Chopper. Both, I understand, had a brief revival about twenty years ago; but the world moves on, and change isn’t always for the worse. Geeks of all ages have plenty of other things to amuse themselves with.

Have you posted something in response to this page?

Feel free to send a webmention

to notify me, giving the URL of the blog or page that refers to

this one.